By Joy Portella—

Former presidential candidate Andrew Yang, whose communication talents and strong social media following were the subject of a recent Goddess Speaks blog, just announced that he’ll become a CNN political commentator. His voice is an important one and we’re happy to hear more of it.

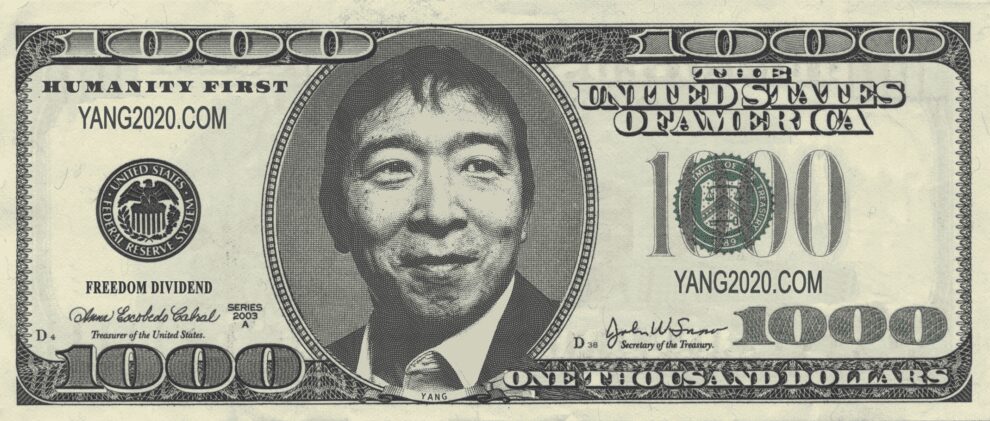

There’s a lot about Yang’s campaign that was appealing but there’s one thing that really stood out: the “Freedom Dividend.” Yang single-handedly got people talking about universal basic income (UBI), which wasn’t mainstream American political thinking or parlance prior to his campaign. Now every serious Democratic presidential contender has a stance on the issue. That’s pretty incredible.

Don’t get me wrong. Andrew Yang didn’t invent UBI. The idea of providing some kind of baseline income for citizens of a particular city, or state, or country has existed for a long time. Italy, where I have the privilege of working for the next several weeks, implemented a UBI scheme last year that allows households making less than €9360 (a little over $10,000) per year to apply for government funds to boost them to that threshold amount. An individual could get almost $850 per month.

The jury’s out on the system’s impact but Italy is one of many places experimenting with this idea. This Vox Future Perfect story details UBI pilot programs around the world. It includes the longest-running UBI scheme in the US—the annual dividend that every person in the state of Alaska receives from the Alaska Permanent Fund, a state-owned investment fund financed by oil revenues. This dividend, which usually ranges $1000-$2000 per year, is different from other UBI interventions because it’s tied to a particular industry but it has been providing a minimum income to Alaskans for nearly 40 years.

Despite UBI’s many fits and starts, nobody really captured the imaginations of Americans before Yang. A September 2019 Hill-HarrisX poll—as Yang was becoming a more visible candidate and his campaign was ramping up—found that 49 percent of Americans were in favor of some form of UBI. That was up from just 6 percent in February 2019.

So what’s different about Yang’s approach?

First, it’s tied to automation and its impact on the American economy, an argument that looms large both on Wall Street and Main Street. Four million U.S. manufacturing jobs have already been automated away, and Yang asserts that this is just the beginning. This is not something we can tariff or subsidize our way out of; it’s inevitable and it’s going to be painful. If we want to come out on the other side of automation with some semblance of civility and economic justice, we need to get on board with a scheme to help people through this transition.

Second, Yang argues that the Freedom Dividend is antipoverty and promises to reduce income inequality. He describes the Dividend as a mechanism to spur a “trickle up economy” that uses a value–added tax on big companies to put money into the hands of people. He went to great lengths to deflect criticism that the Dividend is a socialist measure, arguing that it’s the “next form of capitalism” to ensure income does not start at zero.

You can hear a lot more about the Freedom Dividend in Yang’s own words here.

The final ingredient that Yang added to the UBI conversation is brilliant marketing. “Universal Basic Income” doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue; it’s both wonky and misleading, implying that everyone—including short-term residents—would be eligible to receive funds and creating confusion about who, if anyone, would pay for it. Some UBI proponents are quick to say that the idea needs a rebrand.

And what could be a better rebrand than the “Freedom Dividend?” It plays on both the patriotic attachment to “freedom” that Americans hold so dear and the economic “freedom” that many of us long for. As Yang famously joked: “Who can be against the ‘Freedom Dividend?’ What kind of an asshole do you have to be?” Perhaps more importantly, Yang admitted that he picked the name because it polled well on both the left and the right.

But would the freedom dividend work? Would people save the money? Or use it to pay rent or invest in education or healthcare? Or would people just spend the money on dumb stuff they don’t need or even harmful items like drugs or alcohol?

To answer this question, let’s take a trip to Kenya. UBI has a corollary concept in the foreign aid work and it’s called “cash transfers.” This is the idea that instead of spending money to give people in developing countries a bunch of stuff that we think they need, why not just give people money and let them buy what they actually need?

There’s been a lot of talk in the aid world for the last decade, largely tied to the efforts and rigorous research of a group called GiveDirectly. GiveDirectly focuses exclusively on giving cash installments to people living in poverty, mostly in rural parts of Kenya, and then monitoring the cash’s impact on their lives and the local economy.

I implore you to check out their newsfeed to see what cash recipients are doing with their money—it’s fascinating. Through a series of randomized control trials, GiveDirectly found that—on average $1000 cash infusions lead to $430 increases in assets, $330 increases in nutrition spending, and no additional spending on tobacco or alcohol.

If some of the poorest people in the world can make UBI work, maybe Americans are ready to do the same.