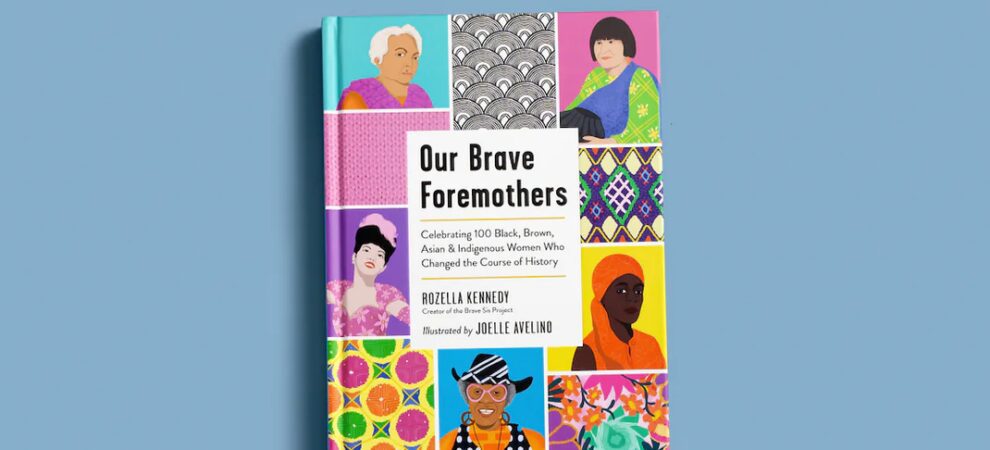

Rozella Kennedy is the Director of Impact and Equity at Camber Collective. Affectionately called Rozie, she has founded three nonprofits and has worked across the arts, environmental, and social service sectors. She is also the creator of Brave Sis Project, a lifestyle brand using wellness and history to build an inclusive sisterhood among Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) women. Rozie’s book, Our Brave Foremothers: Celebrating 100 Black, Brown, Asian, and Indigenous Women Who Changed the Course of History, is available this month!

Minerva’s work with Camber Collective is where we first met Rozie and given her varied and extensive background in storytelling and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion efforts, we had to know more! I was excited to sit with her earlier this year to dive deeper into her story, philosophy, and perspectives on equity in the workplace and in our personal lives. And, of course, explore her new book!

Note: we’ve edited this interview for clarity, but the context—and deep meaning behind Rozie’s work—remains the same.

You are a woman of the world! You have lived in Paris, Santa Fe, and the Bay Area, and grew up in New York. Now you’re in Seattle. I’m curious how have your travels influenced how you connect with people?

I’m about to turn 60, and I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about how it all came together for me. I grew up in New York where I went to an elite all-girls school that changed the entire trajectory of my life. I was around intellectual people—deep thinkers devoted to arts and culture. New York City is also the most diverse city in the world—I was surrounded by a multiplicity of people as the baseline. We call it “code-switching” now, but for me, it was normal to adapt to where I was and who I was surrounded by.

Then, I went to college. In my junior year, I studied in Paris as the only Black woman in the program. Living in Paris was very difficult. In the 80s, the Black population in Paris was largely first or second-generation from the Caribbean or an African country. So, people didn’t know what to do with me as a Black American woman who spoke French. I was treated poorly a lot of the time.

To go from an elite education in New York City, where I was immersed in creative and curious conversations, to living in an environment where I had none of those privileges, I experienced this weird dissonance navigating what felt like opposing worlds.

Eventually, I returned to New York City and started a family with my husband, John Kennedy. He’s a composer and conductor of classical music. As creatives, we accessed spaces with high levels of culture even when we didn’t have money. We could be in these spaces because we were creative people, but then we could return home to a quieter and less extravagant space, as we do now in Seattle. And I feel it’s a privilege. I’m very blessed to have the opportunity to live like this.

Looking back on my years, I see how it all came together for me to be the person I am today. All of my experiences have made me deeply, deeply pluralistic. As a result, I approach people with an open mind and curiosity.

This curiosity comes through in your writing. You speak about the idea of humanized storytelling to create connection with people. What do you mean by that? And what sets humanized storytelling apart from other forms of storytelling?

I believe what Tema Okun says, “the tyranny of the written word is a form of white supremacist culture.” Working with my team at Camber Collective, I say this often. It doesn’t mean that we’re throwing words out the window, but it does mean we must challenge our own creativity to tell stories better. We can humanize a story with photos and quotes to give true voice to the person or focus of our stories.

I believe humanistic creativity does not exist in opposition to professionalism. We lose nothing by including photos or quotes alongside words. We must be mindful that the images we choose do not take on a tokenistic voyeuristic perspective, though. I spend a lot of time curating photos. That’s a part of my job I really like—I look for photos that relate to and evoke the feelings of what we’re trying to convey without upholding a stereotypical story. One of the key pillars of equity and inclusion is being intentional about and accountable to those whose truth is visible in the stories we tell.

I agree. Part of white supremacy is valuing the written word over other forms of communication and truth. But pictures can contribute to inequity and stereotypes. What do you take into consideration when curating images?

I focus on honoring the humanity, dignity, agency, and the unique entity of the human being at the heart of the story. This isn’t easy. No one image could fully illustrate the unique experience of a person. For instance, an image of me could not stand in for a mother in Zimbabwe—we may have similarities, but we are not the same. So, it’s important to choose open-ended and pluralistic images, relevant but not restrictive. A single image cannot carry the responsibility of representing an entire people or story. But it can give us crucial information about the subject of our stories when words are just not enough.

Speaking of combatting white supremacy, I want to explore a quote from your blog series with Camber Collective. In the third blog, you said, “Centering misery over hope, inadvertently, and disproportionately centers dominant culture, whiteness, and patriarchy, as a prime activator of social change…” There’s this idea that pain and suffering fuel social change. How can we use hope and joy as activators of social change?

We have to be deliberate. We live under circumstances that can make this more nuanced, but we have to be deliberate. I’ve heard people say, “you can manifest it, you can call it into being,” and that’s not one hundred percent true. You can’t control what happens to you, but you can control how you respond to it. Our responses and our choices are all we have. I choose to make space for the things that sustain me and fill my cup, so I have the energy to do the personal and transformative work I want to pursue.

That’s how the Brave Sis Project came about. It came from my need to see myself in the wellness space.

Yes! The Brave Sis Project aims to elevate and celebrate BIPOC women in US history and foster a lifestyle of learning and connection among Black, Indigenous, and other women of color. And the next stage in the project is out now: Our Brave Foremothers: Celebrating 100 Black, Brown, Asian, and Indigenous Women Who Changed the Course of History. So, I’m wondering, what is the power of cross-cultural sisterhood?

At the start of this project, I wanted to focus on famous Black women because I’m a Black woman inspired by accomplished Black women. But then it took on a deeper meaning as I started researching women whose stories were not well known. Very quickly, it became less about specific identities of women and woman-identifying people and more about the stories we don’t hear because they have been purposely suppressed. My research was guided by questions like, what could we learn from each other? How could we pause and see that many of our struggles are similar and that we are all pushing toward the same goals? White supremacy has worked to separate us. I wanted to combat that with a powerful vision of BIPOC women coming together across time and culture.

Our Brave Foremothers is an outgrowth of the Brave Sis Project, but it continues to provide space for readers to learn and step into someone else’s story and see themselves reflected. This has been very humbling for many who are so used to whiteness being the default in the narratives we’re told. This book is creating a mindset shift. There is not just one woman at the center, because the center is always moving with every new woman, every new story we step into. This pushes allyship to be more than performative.

Growing up in New York City, my best friends were a Puerto Rican girl and a Filipina girl—we were inseparable. We ate each other’s food, hung out together, and built bonds inclusive of our cultures. That’s the core of who I grew up being and what I wanted for Our Brave Foremothers.