Minerva Strategies is grateful to partner with professionals around the world to create impactful strategies and solutions for social impact organizations. These collaborations lead to innovative approaches and allow us to address our clients’ challenges more thoughtfully and effectively.

We have the immense privilege of working closely with Poché Design Studio, a mission-driven studio founded in Los Angeles, California, founded by Black architects and designers Tobi Ashiru and Morgan Sumner.

The pair crossed paths—literally—in 2016 at the University of Southern California (USC), where they noticed few Black students in their Master of Architecture program and even fewer professional designers. Committed to transforming the field, they dedicated themselves to increasing Black representation in design and architecture while creating compelling design products that serve Black, Indigenous, and communities of color.

We caught up with Tobi and Morgan to discuss design as a tool for change, their motivations, and where they see themselves in five years.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Let’s dive into your background. What are your origin stories?

Morgan Sumner (MS): I graduated from Arizona State University in 2016 with a bachelor’s degree in architectural studies and a minor in African American studies. I immediately got my master’s from USC, where I met Toby. I used all my undergrad knowledge of Blackness and architecture to produce a thesis that was very Black, very kick-ass, and very social.

Tobi Ashiru (TA): Did you mention that you work in architecture?

MS: Laughs. I did not mention anything that I am actively doing. Those degrees did land me a job. In addition to our work at Poché, I am actively pursuing a career in architecture. Currently, I am focusing on what it means to design thoughtful and tasteful spaces for everyone.

TA: I was born in Nigeria and raised in South Africa, where I completed most of my education, including my undergraduate degree in architecture. I then moved to the U.S. and enrolled at USC, where I met Morgan and earned my second degree in architecture. My thesis was also very Black, very fun, and very focused on reclaiming and decolonizing public spaces. In a full circle moment, I now teach at USC.

You both are working professionals running a business, so let’s talk about Poché. What does the name “Poché” mean, and how does it connect to your mission and overall goals?

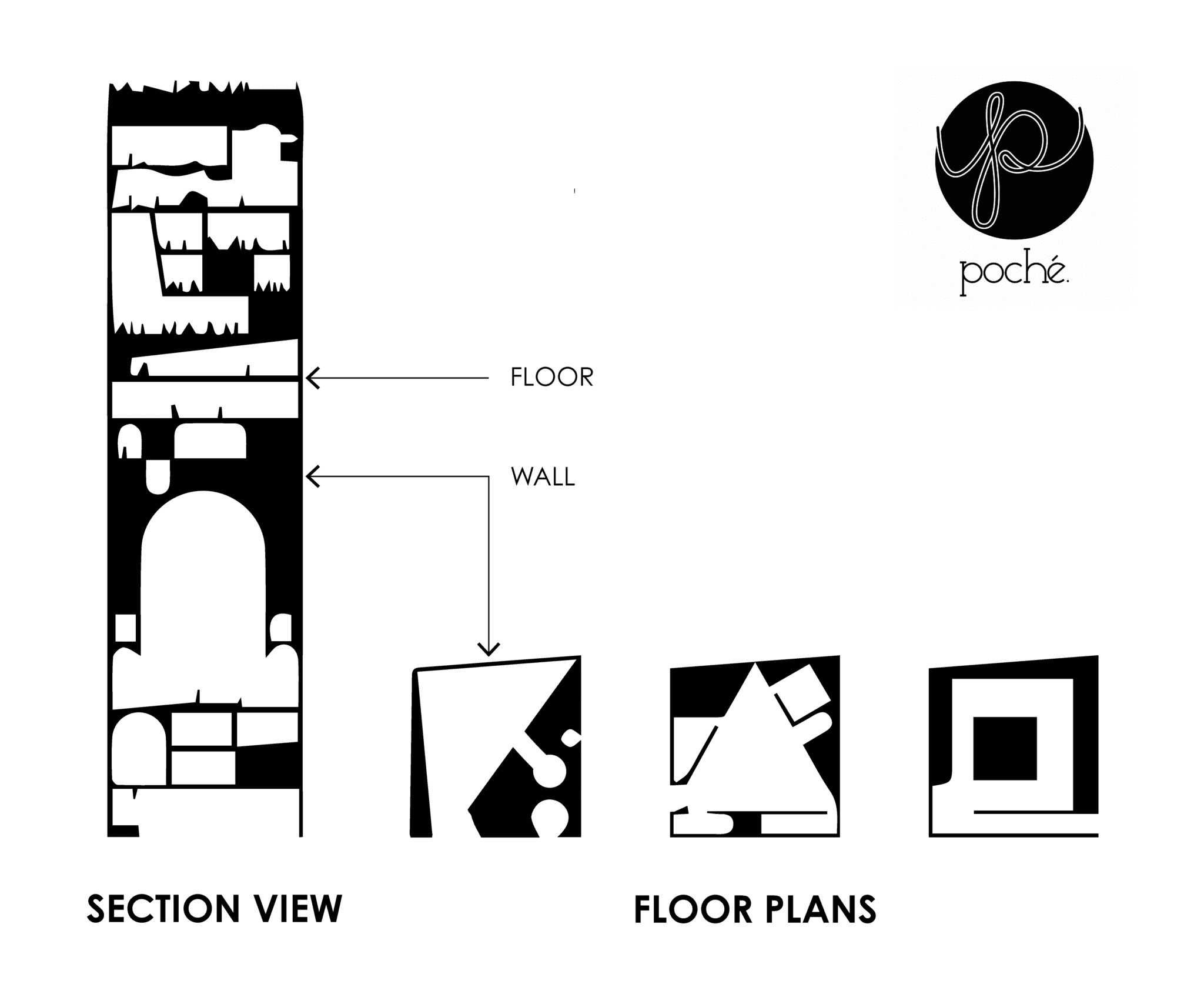

MS: The word itself is an architectural term. It’s defined as the black part of an architectural plan that shows the solid sections and holds all the knowledge.

So, for us to choose that integral part of design speaks directly to the core values of the importance of Blackness in design spaces. Poché anchors us in our foundation and Blackness.

I love how Poché centers both Blackness as a literal and figurative foundation. What about your clients—what makes an organization a great client?

TA: We find that the people we work with best, and work best with us, are mission-driven organizations creating something because they want to improve their communities or drive meaningful change. That’s what our clients have in common and the support our clients usually require typically is centered around visual storytelling.

So how is design and visual storytelling a tool for social change?

MS: Having graphics and images is one thing. But having design as a communication tool is another entirely. There’s rarely ever going to be just one person looking at our clients’ projects. There will be a collection of eyes and opinions, so we have to convey a lot of information intentionally and immediately. Design, especially as a tool for social change, is an amplifier of messages, shaping perceptions and driving understanding on a wide scale.

TA: Vice President Kamala Harris said this poignant phrase that is going viral. She said, “…You think you just fell out of a coconut tree. You exist in the context of all in which you live and what came before you…” That is true of design. Design does not exist in isolation; it is a culmination of the historical, cultural, and social contexts that shape it—we exist within that. Our goal is to create work that people can relate to.

We are grateful to have worked with you on several projects. If you had to choose one project, which would be your favorite?

TA: Seattle Children’s. I love good group work. When everybody is in their zone of genius, playing their part to the highest level, all we can do is win. That project is not only a testament to a solid collaborative process, but it felt good, and that’s what work should feel like.

Seattle Children’s was interesting because they were driven by this desire to improve transparency and accountability specific to equity and anti-racism efforts. They began measuring and tracking progress towards a set of eight outcomes and published a report that did not do what it intended to do. That’s where Minerva and Poché came in. The goal was to develop a new style and approach to sharing Seattle Children’s journey that focused on the primary audiences of this work: workforce members, patients, and families. How did it feel to work on that project?

MS: It was the happiest project! Every single meeting was pure joy. Everyone was proud of the work we were doing. We tackled a very serious topic—equity in health care—but it was a dream project for many reasons. Don’t get me wrong. It was a lot of work and input, but it flowed smoothly. I applaud everyone on that project. From initializing the idea to brainstorming and then enacting the plan—it was a beautiful project.

In the month following the launch of the Health Equity and Anti-Racism (HEAR) annual report, the new landing page was viewed more than 2,600 times—a 130% increase over last year’s results—by more than 1,400 unique users. How did it feel to see the impact of your work?

TA: It’s very affirming. Sometimes, when things are easy, people believe the outcome will be subpar, which is the opposite. Working with Minerva was easy, and so was working with Seattle Children’s. Clients also have a role to play in this achievement. Seattle Children’s really did well by holding themselves accountable by producing the elements we needed to do this work. They held just as much responsibility and accountability as Minerva and Poché.

Everyone on that team did an excellent job! Doing great work is so motivating and I know you both feel the same, but what else motivates you?

MS: In summation, it is joy. Our motivation takes the form of us living fun LA girl lives. But it also means making sure that the people we work with get to live their best lives and feel fully supported.

Okay. One last question. Where will we see Poché in five years?

MS: Oh, wow! Let’s daydream. In five years, we’ll be fresh off the Olympics. I would love for Poché to work on the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. That would be a pivotal moment for us to represent the city that made both of us—that would be incredible.

TA: Abundance, everywhere. I hope our original team members are still with us, but if not, I hope they move on to even better opportunities. Someone described us as a “dope Black girl incubator,” where we set up Black girls for the next level in their careers, helping them understand what they deserve, what they can handle, and how they should be spoken to. So, in five years, I’d like to see us grow and have some of our alumni in cool places.